Osseointegration: The Stuff That Actually Makes Dental Implants Work (And Why You Should Care)

Table of Contents

Now I got you reading the article.

I'll be honest with you: I placed my first dental implant thinking I understood osseointegration. I'd read Brånemark's papers, attended the mandatory lectures, nodded sagely when professors showed histology slides. But it wasn't until my fifth implant failure that I truly understood what was happening at the bone-implant interface.

That failure happened on a Tuesday. I remember because my mother-in-law was visiting, and nothing says "successful clinician" like explaining to your family why Mrs. Gomes needs another surgery. Beer helped that evening. So did finally admitting that I had been confusing "knowing about" osseointegration with actually understanding it.

This article is what I wish someone had written for me 15 years ago. Let's dig in.

The Definition That Changed Everything (And Why Most Clinicians Get It Wrong)

Per-Ingvar Brånemark defined osseointegration in 1977 as "a direct structural and functional connection between ordered, living bone and the surface of a load-carrying implant" (Brånemark et al., 1977).

Here's the thing that took me years to appreciate: this isn't just a fancy definition. It's a functional requirement. The bone doesn't just need to touch the implant—it needs to carry load through that connection. This distinction separates successful implant dentistry from expensive tooth extractions followed by metal insertion.

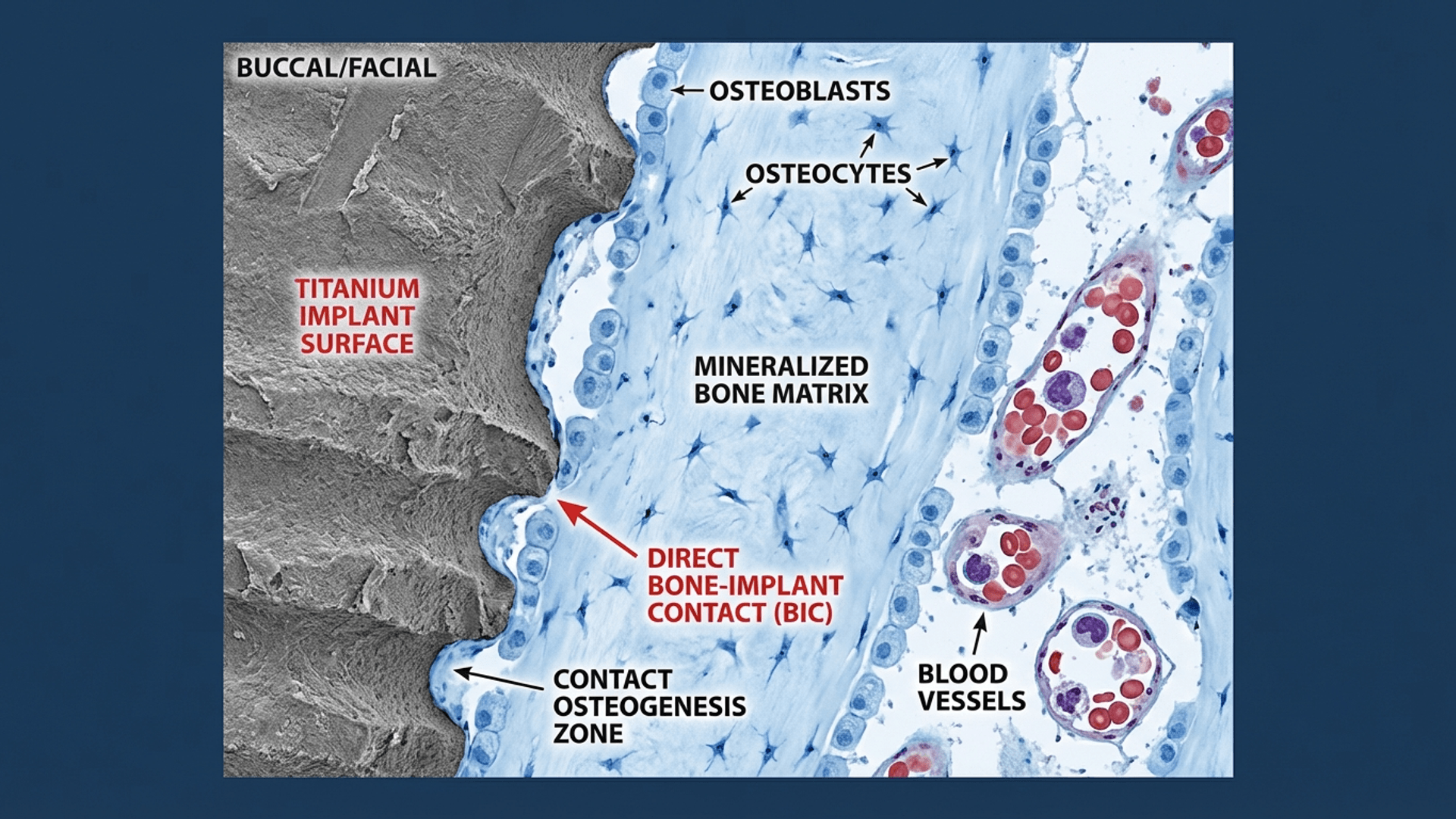

At the histological level, osseointegration means direct bone-to-implant contact (BIC) without intervening fibrous tissue. When you get fibrous encapsulation instead? That's your implant telling you it has become an expensive failure, similar to rejected orthopedic devices.

The percentage of bone-to-implant contact varies: 60-70% BIC in cortical bone, 30-40% in trabecular bone (Lekholm & Zarb, 1985). But here's what nobody tells you in dental school: these percentages matter less than the quality of that contact. I've seen implants fail at 70% BIC and succeed at 40%. Context is everything.

Related: If you want to understand what happens to bone before you even place an implant, read my guide on bone remodeling after tooth extraction—it's foundational knowledge most courses skip. Also essential: our complete guide to socket preservation, which covers how to maintain the alveolar ridge after extraction so you have the best possible site for osseointegration.

The Accidental Discovery: How a Failed Experiment Changed Medicine

Let me tell you a story that should give hope to every clinician who's ever had an "oops" moment in the operatory.

In 1952, Per-Ingvar Brånemark was a Swedish orthopedic surgeon studying bone marrow blood flow in rabbit tibias. He was using titanium optical chambers—basically tiny microscopes he'd implanted in the bone to observe blood flow.

Here's where it gets interesting: when he tried to retrieve these chambers months later, they were stuck. Completely fused to the bone. His expensive research equipment was now permanently part of his rabbits.

Most researchers would have called this a failure. Brånemark looked at those stuck chambers and thought: "What if this isn't a bug—it's a feature?"

Thirteen years. That's how long Brånemark spent investigating this "accident" before placing the first dental implant in a human patient, Gösta Larsson, in 1965. Gösta kept those implants for over 40 years until his death in 2006.

This is why I tell my residents: document your failures. Your complications might be someone else's breakthrough.

The Four Phases of Osseointegration: What's Actually Happening in There

Understanding the biological cascade following implant placement isn't just academic masturbation—it's directly relevant to every clinical decision you'll make. Here's what's actually happening while your patient thinks you're just "letting the bone heal."

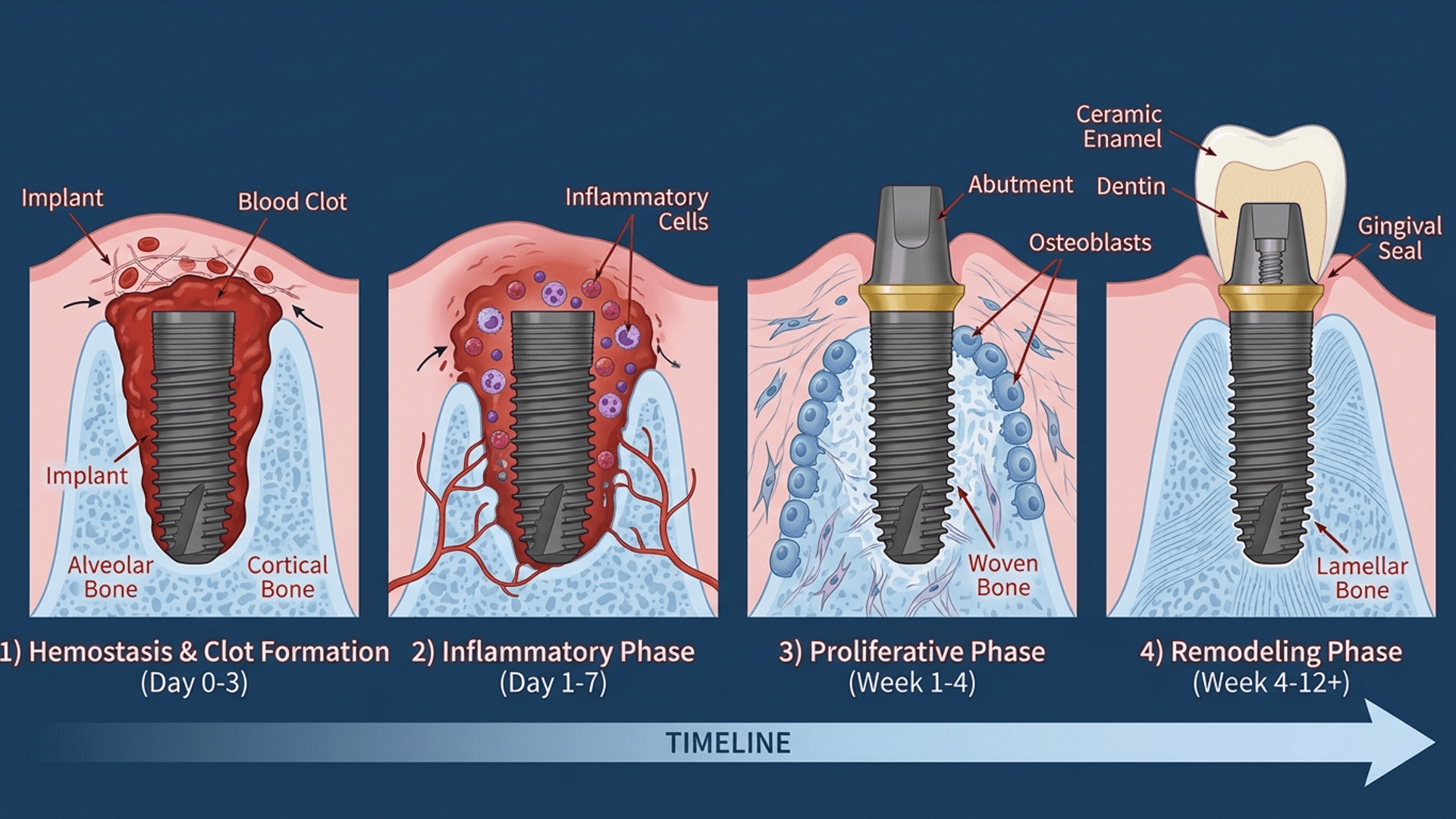

I created this animation to help visualize the osseointegration process—it shows exactly what's happening at the cellular level:

Phase 1: Hemostasis (Minutes to Hours) – The Blood Bath

The moment your implant touches living tissue, all hell breaks loose. Blood from disrupted vessels contacts the titanium surface, initiating the clotting cascade.

Platelets rush to the scene like paparazzi at a celebrity scandal:

- Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)

- Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β)

- Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)

These growth factors recruit inflammatory cells and prime the wound for healing. That blood clot around your freshly placed implant? It's not a complication—it's a provisional matrix for cellular migration. Don't disturb it.

Phase 2: Inflammation (Days 1-7) – The Cleanup Crew

Neutrophils arrive within hours, followed by macrophages that dominate this phase. They're clearing debris and necrotic bone fragments created during your drilling.

Here's what I didn't appreciate early in my career: macrophage phenotype matters enormously. M1 (pro-inflammatory) macrophages initially dominate, but you need a timely switch to M2 (pro-healing) phenotype for successful osseointegration.

The inflammatory response to titanium is notably subdued compared to other materials. This is why we use titanium, not stainless steel or chromium-cobalt. Titanium's biocompatibility stems from its stable oxide layer (TiO₂), which forms spontaneously upon exposure to air and regenerates within nanoseconds if disrupted.

Think about that: nanoseconds. Your implant surface is essentially self-healing at the molecular level.

Phase 3: Proliferation (Weeks 1-4) – Building the House

This is where the magic happens. Mesenchymal stem cells migrate to the implant surface and differentiate into osteoblasts under the influence of bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs).

Two distinct pathways occur simultaneously—and understanding both transformed my approach to immediate implant placement:

Distance Osteogenesis: New bone forms from the osteotomy walls and grows toward the implant. This is what happens with machined (smooth) implant surfaces. Slow, predictable, boring.

Contact Osteogenesis: Osteogenic cells migrate directly onto the implant surface and deposit bone matrix outward. Modern surface modifications significantly enhance this pathway. Faster, cooler, what we want.

By weeks 3-4, woven bone has filled the gap between implant and native bone. This is primary mechanical stability transforming into something biological.

Phase 4: Remodeling (Weeks 4-52+) – Organized Chaos

Woven bone gets replaced by organized lamellar bone through osteoclast-osteoblast coupling. This remodeling continues for months to years, responding to functional loading according to Wolff's law.

Here's the clinical insight that changed my practice: the "stability dip" around weeks 3-4. Primary stability decreases as bone remodels. Secondary stability increases as new bone matures. Plot them together and you'll see why immediate loading protocols are so specific about timing.

Factors That Actually Affect Osseointegration (Evidence, Not Opinion)

I've attended conferences where speakers claim their special technique or magic sauce is the key to successful osseointegration. Usually, they're selling something. Here's what the evidence actually shows.

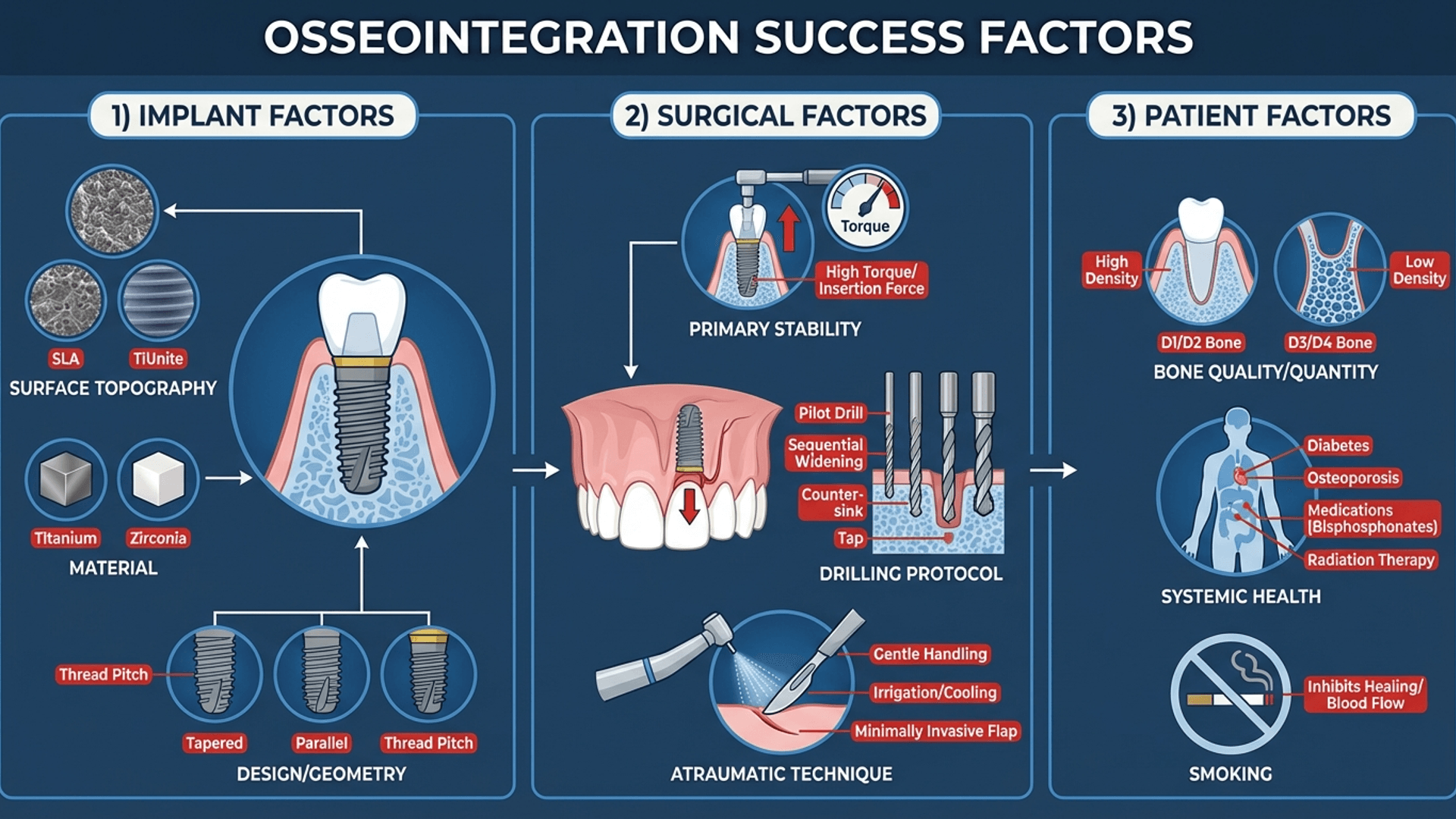

Implant Surface: This Matters More Than Brand

Surface topography is the most modifiable factor affecting osseointegration. Your implant brand matters less than its surface characteristics. I know this bothers people who've built their identity around one system, but the science is clear.

Surface Roughness Categories (Wennerberg & Albrektsson, 2009):

| Category | Sa Value | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Smooth | <0.5 μm | Machined/turned |

| Minimally rough | 0.5-1.0 μm | Acid-etched alone |

| Moderately rough | 1.0-2.0 μm | SLA, TiOblast, Osseotite, TiUnite, TiUltra |

| Rough | >2.0 μm | Plasma-sprayed TPS |

Moderately rough surfaces (Sa 1.0-2.0 μm) win. Too smooth and bone can't grip it. Too rough and you're setting up for peri-implantitis down the road.

If you want to geek out on surfaces: Read my deep dive on whether dental implant surfaces are really all the same. Spoiler: they're not.

Hydrophilic modifications (SLActive, TiUnite) accelerate early osseointegration by improving blood wetting and protein adsorption. Clinical studies show faster bone formation, potentially allowing earlier loading protocols (Lang et al., 2011).

Primary Stability: The Non-Negotiable

Primary stability refers to mechanical engagement at placement. It's determined by bone density/quality, implant design (threads, taper), surgical technique, and implant-to-osteotomy fit.

Why does this matter? Micromotion exceeding 50-150 μm during healing leads to fibrous encapsulation rather than osseointegration (Brunski, 1999). Your implant becomes a very expensive tooth-shaped failure.

Assessment Methods:

- Insertion Torque: 25-45 Ncm generally indicates adequate stability

- Resonance Frequency Analysis (RFA): ISQ values 60-80 = good stability

- Periotest: Lower values = higher stability

I measure every implant. The one time you skip it will be the one that fails.

Surgical Technique: You're Part of the Equation

Atraumatic surgery isn't a buzzword—it's the difference between success and explanation letters.

Drilling Protocol: Sequential drilling with copious irrigation prevents thermal necrosis. Bone cell death occurs at 47°C for 1 minute (Eriksson & Albrektsson, 1983). That's not very hot. Sharp drills, intermittent motion, internal/external irrigation.

Implant Bed Preparation: Underprepare slightly (final drill 0.2-0.5 mm smaller than implant diameter). This enhances primary stability through press-fit. But don't overdo it—excessive torque causes microfractures.

For immediate implant situations: Understanding bundle bone and gap management is essential. This changed how I approach extraction sockets entirely.

Patient Factors: The Variables You Can't Control (But Can Assess)

Diabetes Mellitus: Poorly controlled (HbA1c >8%) impairs healing and increases failure risk. Well-controlled diabetics achieve comparable success rates (Moraschini et al., 2016). Always ask about HbA1c.

Smoking: This is the one I'll argue about with patients. Tobacco use significantly impairs osseointegration through vasoconstriction, reduced osteoblast function, and compromised immune response. Failure rates are 2-3 times higher in smokers. I tell smokers: quit 4 weeks before surgery, stay quit 8 weeks after. Or accept the higher risk.

Osteoporosis: Systemic bone density doesn't directly correlate with jaw bone quality, but bisphosphonate therapy requires careful consideration due to MRONJ risk.

Radiation Therapy: Previous head and neck radiation compromises bone vascularity. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy may improve outcomes in irradiated bone.

Clinical Assessment: How Do You Know It Actually Worked?

You can't directly visualize the bone-implant interface in a living patient. But several methods give you clinically useful information.

Resonance Frequency Analysis (RFA)

RFA uses a SmartPeg attached to the implant to measure resonance frequency, expressed as an Implant Stability Quotient (ISQ) from 1-100.

ISQ Interpretation (what I actually use clinically):

- <60: Low stability. Extend healing time. Don't be a hero.

- 60-70: Medium stability. Adequate for most situations.

- >70: High stability. Green light for loading.

The real value of RFA is longitudinal monitoring. A decreasing ISQ trend tells you something's wrong before the patient complains.

Insertion Torque

Immediate feedback at placement. Values between 25-45 Ncm indicate adequate bone engagement. But higher isn't always better—excessive torque causes microfractures.

Radiographic Assessment

Periapical radiographs can't visualize osseointegration directly but can identify marginal bone loss patterns, peri-implant radiolucencies, and progressive bone loss.

A thin radiolucent line completely surrounding an implant? That's fibrous encapsulation. That implant is not osseointegrated, regardless of what you want to believe.

Loading Protocols: When Can You Actually Use the Implant?

Brånemark's original protocol required 3-6 months of submerged healing. Current evidence supports more aggressive approaches in appropriate situations.

Immediate Loading (Within 48 Hours)

Well-documented for full-arch rehabilitation (All-on-4/All-on-6), single anterior teeth with adequate primary stability, and overdentures on multiple implants.

Requirements: excellent primary stability (>35 Ncm, ISQ >70), adequate bone quality, appropriate occlusal scheme.

Early Loading (1-8 Weeks)

Success comparable to conventional loading in systematic reviews. Balances faster treatment completion against biological healing requirements.

Conventional Loading (3-6 Months)

Still appropriate for compromised bone quality, grafted sites, medically compromised patients, and lower primary stability.

The Dunning-Kruger effect applies here: The more you learn about loading protocols, the more conservative you become in complex cases. Early in my career, I immediate-loaded everything. Now I wait when the biology tells me to wait.

Optimizing Osseointegration: My Clinical Checklist

Based on current evidence and too many learning experiences, here's my protocol:

Preoperative:

- CBCT assessment (always)

- Identify anatomical structures

- Consider guided surgery for complex cases

- Assess patient risk factors honestly

Surgical:

- Atraumatic flap elevation

- Controlled drilling with irrigation (≤800 rpm initially)

- Final drill selection based on bone density

- Confirm primary stability before closure

- Document with RFA measurement

Postoperative:

- Antibiotic prophylaxis (I know it's controversial—I consider patient factors)

- Chlorhexidine rinses

- Soft diet during initial healing

- Smoking cessation counseling (again)

- Follow-up at 4-6 weeks for stability trend

Future Directions: What's Coming

Bioactive Surface Coatings: Growth factor incorporation, antimicrobial peptides, bioactive molecules. Early research is promising.

3D-Printed Patient-Specific Implants: Custom implants matching defect anatomy. Particularly interesting for compromised sites.

Immunomodulation: Understanding and potentially manipulating the immune response to titanium could enhance healing in compromised patients.

Zirconia Implants: Ceramic implants offer esthetic advantages. Research continues to optimize surface treatments for comparable osseointegration to titanium.

Key Takeaways (The Stuff That Actually Matters)

1. Osseointegration is predictable when you optimize patient selection, surgical technique, and loading protocols

2. Surface characteristics matter more than implant brand for bone response

3. Primary stability is non-negotiable for successful osseointegration

4. Atraumatic surgery preserving bone viability is as important as implant selection

5. Loading protocols should be individualized based on stability measurements and patient factors

6. Longitudinal monitoring with RFA can identify problems before clinical failure

Understanding osseointegration empowers evidence-based decisions at every stage of implant treatment. It took me a few failures, some uncomfortable conversations with patients, and many beers with colleagues to truly appreciate this.

I hope this article saves you at least one of those failures.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does osseointegration take to complete?

The initial osseointegration period typically requires 6-12 weeks for adequate bone-to-implant contact to develop. However, bone remodeling continues for 12-18 months as woven bone matures into organized lamellar bone. Factors affecting timeline include bone quality, implant surface, and patient health status.

What is a good ISQ value for dental implants?

ISQ values above 60 generally indicate adequate implant stability suitable for most loading protocols. Values between 70-80 represent excellent stability often permitting immediate or early loading. Values below 55 suggest extended healing may be advisable. Trend monitoring over time provides more useful information than single measurements.

Can osseointegration fail after years of successful function?

Yes, late implant failure can occur even after years of successful osseointegration. Causes include peri-implantitis (bacterial infection causing bone loss), occlusal overload, and systemic health changes. Regular maintenance and monitoring help identify problems early when intervention is most effective.

What percentage of bone-to-implant contact is considered successful?

Studies show well-integrated implants typically demonstrate 60-70% bone-to-implant contact in cortical bone and 30-40% in trabecular regions. Complete 100% contact is neither achieved nor required for clinical success. The quality and organization of bone contact matters as much as percentage.

Does smoking affect osseointegration?

Smoking significantly impairs osseointegration through multiple mechanisms including vasoconstriction, reduced osteoblast activity, and compromised immune function. Studies consistently show implant failure rates 2-3 times higher in smokers. Smoking cessation 4 weeks before and 8 weeks after surgery may improve outcomes.

What is the difference between primary and secondary stability?

Primary stability refers to mechanical engagement at implant placement, determined by press-fit between implant and bone. Secondary stability develops through biological osseointegration as new bone forms around the implant. Primary stability decreases during remodeling while secondary stability increases, with a stability "dip" typically occurring around weeks 3-4.

References

Brånemark, P. I., Hansson, B. O., Adell, R., Breine, U., Lindström, J., Hallén, O., & Ohman, A. (1977). Osseointegrated implants in the treatment of the edentulous jaw. Experience from a 10-year period. Scandinavian Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 16, 1-132.

Brunski, J. B. (1999). In vivo bone response to biomechanical loading at the bone/dental-implant interface. Advances in Dental Research, 13(1), 99-119.

Eriksson, A. R., & Albrektsson, T. (1983). Temperature threshold levels for heat-induced bone tissue injury: A vital-microscopic study in the rabbit. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 50(1), 101-107.

Lang, N. P., Salvi, G. E., Huynh-Ba, G., Ivanovski, S., Donos, N., & 3. Bosshardt, D. D. (2011). Early osseointegration to hydrophilic and hydrophobic implant surfaces in humans. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 22(4), 349-356.

Lekholm, U., & Zarb, G. A. (1985). Patient selection and preparation. In P. I. Brånemark, G. A. Zarb, & T. Albrektsson (Eds.), Tissue-integrated prostheses: Osseointegration in clinical dentistry (pp. 199-209). Quintessence.

Moraschini, V., Barboza, E. S., & Peixoto, G. A. (2016). The impact of diabetes on dental implant failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 45(10), 1214-1220.

Wennerberg, A., & Albrektsson, T. (2009). Effects of titanium surface topography on bone integration: A systematic review. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 20(s4), 172-184.

Comments

0 totalLoading comments...

Previous

The 2018 AAP/EFP Periodontal Classification: A Clinician's Complete Guide to Staging and Grading

Next

Socket Preservation: The Complete 2026 Guide to Alveolar Ridge Preservation Techniques

Related Articles

Machine Learning for Dentists: Predicting Implant Success with AI

1 min read

Socket Preservation: The Complete 2026 Guide to Alveolar Ridge Preservation Techniques

21 min read